PUSHING TO THE FRONT

OR, SUCCESS UNDER DIFFICULTIES

A BOOK OF INSPIRATION AND ENCOURAGEMENT TO

ALL WHO ARE STRUGGLING FOR SELF-ELEVATION

ALONG THE PATHS OF KNOWLEDGE

AND OF DUTY

BY

ORISON SWETT MARDEN

By The Author of Architects of Fate

AUTHOR OF "RISING IN THE WORLD OR, ARCHITECTS OF FATE."

EDITOR OF " SUCCESS," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED WITH TWENTY-FOUR FINE

PORTRAITS OF EMINENT PERSONS

|

We live in a new and exceptional age. America is another name for Opportunity. Our whole history appears like a last effort of the Divine Providence in behalf of the human race. ....................................................EMERSON |

by www.arfalpha.com

NEW YORK.

THOMAS Y. ROWELL & CO.

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1894

BY ORISON SWETT MARDEN,

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

| BOOKS BY ORISION SWETT MARDEN | |

| Pushing to the Front; or, Success Under Difficulties 12mo, with portraits $1.50 | |

| Rising in the World; or, Architects of Fate 12mo, with portraits $1.50 | |

| The Secret of Achievement 12mo, with portraits $1.50 | |

| Talks with Great Workers 12mo, with portraits $1.50 | |

| Success Booklets | |

| Character | Opportunity |

| Cheerfulness | Iron Will |

| Good Manners | Economy |

| 12mo, ornamental white binding Per volume, 35 cents | |

| 12mo, cloth, illustrated with portraits Per Volume, 50 cents | |

| CONTENTS. | ||

| CHAPTER | Page | |

| I. | THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY . . . . . . . | 5 |

| Don't wait for your opportunity : make it. | ||

| II. | Boys WITH NO CHANCE . . . . . . . . . . . | 25 |

| Necessity is the priceless spur. | ||

| II. | AN IRON WILL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | |

| Give a youth resolution and the alphabet, and who shall place limits to his career? | ||

| IV. | POSSIBILITIES IN SPARE MOMENTS . . . . . . | 63 |

| If in a genius like Gladstone carries through life a book his pocket, lest an unexpected spare moment slip from his grasp, what should we of common abilities not resort to, to save the precious moments from oblivion ? | ||

| V. | ROUND BOYS IN SQUARE HOLES . . . . . . . . | 74 |

| Man is doomed to perpetual inferiority and disappointment if out of his place, and gets his living by his weakness instead of by his strength. | ||

| VI. | WHAT CAREER? . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 89 |

| Your talent is your call. " What can you do? " is the interrogation of the century. Better adorn your own than seek another's place. | ||

| VII. | CONCENTRATED ENERGY . . . . . . . . . . . | 106 |

| One unwavering aim. Don't dally with your purpose. Not many things indifferently, but one thing supremely. | ||

| VIII. | ON TIME," OR THE TRIUMPH of PROMPTNESS . . | 121 |

| Don't brood over the past or dream of the future; but seize the instant, and get your lesson from the hour | ||

| IX. | CHEERFULNESS AND LONGEVITY . . . . . . . . | 133 |

| You must take joy with you, or you will not find it even in heaven. | ||

| X. | A FORTUNE IN GOOD MANNERS . . . . . . . . | 148 |

| The good-mannered can do without riches: all doors fly open to them, and they enter everywhere without money and without price. | ||

| XI. | THE TRIUMPHS of ENTHUSIASM . . . . . . . . | 170 |

| " What are hardships, ridicule, persecution, toil, sickness, to a soul throbbing with an overmastering enthusiasm?" | ||

| XII. | TACT OR COMMON SENSE . . . . . . . . . . . | 187 |

| Talent is no match for tact ; we see its failure everywhere. In | ||

| the race of life, common sense has the right of way. |

| CONTENTS. | ||

| CHAPTER | Page | |

| XIII. | SELF-RESPECT AND SELF-CONFIDENCE ..... | 202 |

| We stamp our own value upon ourselves, and cannot expect to pass for more. | ||

| XIV. | GREATER THAN WEALTH . . . . . . . . | 210 |

| A man may make millions and be a failure still. He is the richest man who enriches mankind most | ||

| XV | THE PRICE OF SUCCESS . . . . . . | 232 |

| "Work or starve" is nature's motto, it is written on the stars and the sod alike, - starve mentally, starve morally, starve physically. | ||

| XVI. | CHARACTER IS POWER . . . . . . . . | 250 |

| Beside the character of a Washington the millions of many an American look contemptible. Character is success, and there is no other | ||

| XVII. | ENAMORED OF ACCURACY . . . . . . . . . . | 273 |

| Twenty things half done do not make one thing well done. There is a great difference between going just right and a little wrong. | ||

| XVIII. | LIFE IS WHAT WE MAKE IT . . . . . . . . . | 292 |

| We get out of life just what we put into it. The world has for us just what we have for it. | ||

| XIX. | THE VICTORY IN DEFEAT . . . . . . . . ... | 304 |

| To know how to wring victory from our defeats, and make steppingstones of our stumbling-blocks, is the secret of success. | ||

| XX. | NERVE-GRIT, GRIP, PLUCK. . . . . . . . . | 318 |

| There is something grand and inspiring in a young man who fails squarely after doing his level best, and then enters the con test a second and a third time with undaunted courage and re doubled energy. | ||

| XXI. | THE REWARD OF PERSISTENCE . . . . . . . . | 337 |

| "Mere genius darts, flutters, and tires; but perseverance wears and wins." | ||

| XXII. | A LONG LIFE, AND HOW TO REACH It. . . . . | 356 |

| The first requisite to success is to be a first-class animal. Even the greatest industry cannot amount to much, if a feeble body does not respond to the ambition. | ||

| XXIII. | BE BRIEF . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 372 |

| "Brevity is the soul of wit." Boil it down. | ||

| XXIV | ASPIRATION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 375 |

| A man cannot aspire if he looks down." Look upward, live upward. | ||

| XXV. | THE ARMY OF THE RESERVE . . . . . . . . | 389 |

| We never can tell what is in a man until an emergency calls out his reserve, and he cannot call out an ounce more than has been stored up. |

| LIST OF PORTRAITS. | |

| PAGE | |

| ABRAHAM LINCOLN. From an original unretouched negative ,made in 1864, at the time the President commissioned Ulysses S. Grant lieutenant-general and commander of all the armies of the republic. It is said that this negative, with one of General Grant, was made in commemoration of that event. Frontispiece. | |

| NAPOLEON. After Painting by Charles de Chatillon . . . . | 6 |

| BENJAMIN FRANKLIN. After Painting by Desnoyers . . . | 24 |

| BISMARCK. After the Lenbach Portrait . . . . . . . . | 54 |

| HARRIET BEECHER STOWE. After an English Engraving by R. Young, from an original portrait taken about the time that "Uncle Tom's Cabin" was published . . | 62 |

| JAMES WATT. After an English Engraving . . . . . . . | 74 |

| FRANCIS PARKMAN. After Photograph . . . . . . . . | 106 |

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS. After Painting by Healy in Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D. C. . . . . . . . . . | 120 |

| OLIVER WENDELL HOLMES. After Photograph . . . . . | 132 |

| MADAME DE STAEL, After Painting by Baron Francois Gerard | 146 |

| SIR HUMPHRY DAVY. After Painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 170 |

| HORACE GREELEY. After Photograph . . . . . . . . | 186 |

| GEORGE PEABODY. After Photograph . . . . . . . . . | 202 |

| WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON. After Photograph . . . . . | 210 |

| PROFESSOR S. F. B.. MORSE. After Photograph . . . . . | 232 |

| GEORGE WASHINGTON. After the Stuart Painting in Museum Flue Arts, Boston . | 250 |

| GALILEO GALILEI. After Painting by Sustermans in the Ufizzi Palace, Florence . . | 272 |

| HENRY WARD BEECHER. After Etching by Rajon . . . . | 292 |

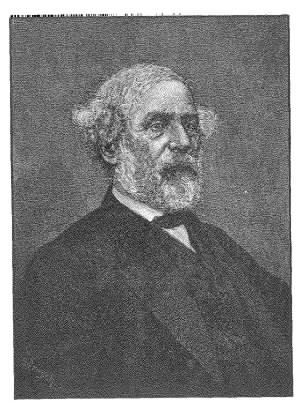

| GENERAL ROBERT E. LEE. After Photograph . . . . . . | 304 |

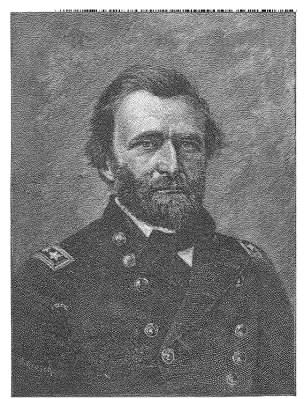

| GENERAL ULYSSES S. GRANT. After Photograph. . . . . | 318 |

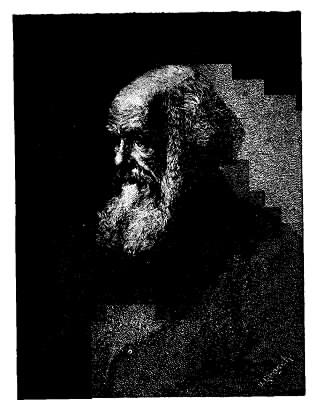

| CHARLES ROBERT DARWIN. After an Etching by Rajon . . | 336 |

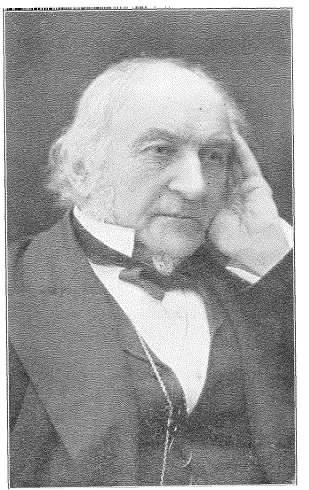

| WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE. After Photograph . . . . | 356 |

| DAVID GLASGOW FARRAGUT. After Treasury Department Engraving . . . . . | 374 |

| DANIEL WEBSTER. After Daguerreotype . . . . . . . . | 388 |

| Most of these portraits are from original sources, and have neve been used before |

Abraham Lincoln

"With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in."

PREFACE.

The author's excuse for one more postponement of the end " of making many books " can be briefly, given. He early determined that if it should ever lie in his power, he would write a book to encourage, inspire, and stimulate boys and girls who long to be somebody and do something in the world, but feel that they have no chance in life. Among hundreds of American and English books for the young, claiming to give the "secret of success," he found but few which satisfy the cravings of youth, hungry for stories of successful lives, and eager for every hint and every bit of information which may help them to make their way in the world. He believed that the power of an ideal book for youth should lie in its richness of concrete examples, as the basis and inspiration of character-building; in its uplifting, energizing, suggestive force, more than in its arguments; that it should be free from materialism, on the one hand, and from cant on the other; and that it should abound in stirring examples of men and women who have brought things to pass. To the preparation of such a book he had devoted all his spare moments for ten years, when a fire destroyed all his manuscript and notes. The memory of some of the lost illustrations of difficulties overcome stimulated to another attempt; so once more the gleanings of odd bits of time for years have been arranged in the following pages.

The author's aim has been to spur the perplexed youth to act the Columbus to his own undiscovered possibilities; to urge him not to brood over the past, nor dream of the future, but to get his lesson from the hour; to encourage him to make every occasion a great occasion, for he cannot tell when fate may take his measure for a higher place; to show him that he must not wait for his

IV PREFACE.

opportunity, but make it; to tell the round boy how he may get out of the square hole, into which he has been wedged by circumstances or mistakes; to help him to find his right place in life; to teach the hesitating youth that in a land where shoemakers and farmers sit in Congress no limit can be placed to the career of a determined youth who has once learned the alphabet. The standard of the book is not measured in gold, but in growth; not in position, but in personal power; not in capital, but in character. It shows that a great checkbook can never make a great man; that beside the character of a Washington, the millions of a Croesus look contemptible; that a man may be rich without money, and may succeed though he does not become President or member of Congress; that he who would grasp the key to power must be greater than his calling, and resist the vulgar prosperity that retrogrades toward barbarism; that there is something greater than wealth, grander than fame; that character is success, and there is no other.

If this volume shall open wider the door of some narrow life, and awaken powers before unknown, the author will feel repaid for his labor. No special originality is claimed for the book. It has been prepared in odd moments snatched from a busy life, and is merely a new way of telling stories and teaching lessons that have been told and taught by many others from Solomon down. These well-worn and trite topics lie " the marrow of the wisdom of the world."

"Though old the thought, and oft expressed, 'T is his at last who says it best."

If in rewriting this book from lost manuscript, the author has failed to always give due credit, he desires to hereby express the fullest obligation. He also wishes to acknowledge valuable assistance from Mr. Arthur W. Brown, of West Kingston, R. I. 43 BowDois Street, Boston, November 11, 1894.

PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

CHAPTER I.

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY

No man is born into this world whose work is not born with him. - LOWELL.

No royal permission is requisite to launch forth on the broad sea of discovery that surrounds us-most full of novelty where most explored.- EDWARD EVERETT.

Things don't turn up in this world until somebody turns them up. - GARFIELD.

We live in a new and exceptional age. America is another name for Opportunity. Our whole history appears like a last effort of the Divine Providence in behalf of the human race.- EMERSON.

Vigilance in watching opportunity ; tact and daring in seizing upon opportunity; force and persistence in crowding opportunity to its utmost of possible achievement-these are the martial virtues which must command success. - AUSTIN PHELPS.

"I will find away or make one."

There never was a day that did not bring its own opportunity for doing good, that never could have been done before, and never can be again. - W. H. BURLEIGIH.

"Are you in earnest? Seize this very minute;

What you can do, or dream you can, begin it."

" IF we succeed, what will the world say?" asked Captain Berry in delight, when Nelson had explained his carefully formed plan before the battle of the Nile.

"There is no if in the case," replied Nelson. "That we shall succeed is certain. Who may live to tell the tale is a very different question." Then, as his captains rose from the council to go to their respective ships, he added: "Before this time tomorrow I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey." His quick eye and daring spirit saw an opportunity of glorious victory where others saw only probable defeat.

6 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

" Is it POSSIBLE to cross the path ? " asked Napoleon of the engineers who had been sent to explore the dreaded pass of St. Bernard. "Perhaps," was the hesitating reply, "it is within the limits of possibility." "FORWARD, THEN," said the Little Corporal, heeding not their account of difficulties, apparently insurmountable.

England and Austria laughed in scorn at the idea of transporting across the Alps, where "no wheel had ever rolled, or by any possibility could roll," an army of sixty thousand men, with ponderous artillery, and tons of cannon balls and baggage, and all the bulky munitions of war. But the besieged Massena was starving in Genoa, and the victorious Austrians thundered at the gates of Nice. Napoleon was not the man to fail his former comrades in their hour of peril.

The soldiers and all their equipments were inspected with rigid care. A worn shoe, a torn coat, or a damaged musket was at once repaired or replaced, and the columns swept forward, fired with the spirit of their chief.

"High on those craggy steeps, gleaming through the mists, the glittering bands of armed men, like phantoms, appeared. The eagle wheeled and screamed beneath their feet.

The mountain goat, affrighted by the unwonted spectacle, bounded away, and paused in bold relief upon the cliff to gaze at the martial array which so suddenly had peopled the solitude. When they approached any spot of very special difficulty, the trumpets sounded the charge, which reechoed with sublime reverberations from pinnacle to pinnacle of rock and ice.

Everything was so carefully arranged, and the influence of Napoleon so boundless, that not a soldier left the ranks. Whatever obstructions were in the way were to be at all hazards surmounted, so that the long file, extending nearly twenty miles, might not be thrown into confusion." In four days the army was marching on the plains of Italy.

NAPOLEON

| "There shall be no Alps." Impossible is a word to be found only in the dictionary of fools, |

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 7

When this "impossible" deed was accomplished, others saw that it might have been done long before. Many a commander had possessed the necessary supplies, tools, and rugged soldiers, but lacked the grit and resolution of Bonaparte. Others excused themselves from encountering such gigantic obstacles by calling ; them insuperable. He did not shrink from mere difficulties, however great, but out of his very need made and mastered his opportunity.

Grant at New Orleans had just been seriously injured by a fall from his horse, when he received orders to take command at Chattanooga, so sorely beset by the Confederates that its surrender seemed only a question of a few days, for the hills around were all aglow by night with the campfires of the enemy, and supplies had been cut off. Though in great pain, General Grant gave directions for his removal to the new scene of action immediately.

On transports up the Mississippi, the Ohio, and one of its tributaries; on a litter borne by horses for many miles through the wilderness; and into the city at last on the shoulders of four men, he was taken to Chattanooga. Things assumed a different aspect immediately. A Master had arrived who was equal to the situation. The army felt the grip of his power. Before he could mount his horse, he ordered an advance. Soon the surrounding hills were held by Union soldiers, although the enemy contested the ground inch by inch.

Were these things 'the result of chance, or were they compelled by the indomitable determination of the injured General ?

Did things adjust themselves when Horatius with two companions held ninety thousand Tuscans at bay until the bridge across the Tiber had been destroyed ? - when Leonidas at Thermopylae checked the mighty march of Xerxes ? - when Themistocles, off the coast of Greece, shattered the Persian's Armada? - when Caesar,

8 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

finding his army hard pressed, seized spear and buckler fought while he reorganized his men, and snatched victory from defeat ? -when Winkelried gathered to his breast a sheaf of Austrian spears, thus opening a path through which his comrades pressed to freedom? when Benedict Arnold, by desperate daring at Saratoga, won the battle which seemed doubtful to Horatio Gates, loitering near his distant tent ?-when for years, Napoleon did not lose a single battle in which he was personally engaged ? - when Wellington fought in many climes without ever being conquered ? - when Ney, on a hundred fields, changed apparent disaster into brilliant triumph ? - when Perry left the disabled Lawrence, rowed to the Niagara, and silenced the British guns? -when Sheridan arrived from Winchester just as the Union retreat was becoming a rout, and turned the tide by riding along the line ? -when Sherman signaled his men to hold the fort, though sorely pressed; and they held it, knowing that their leader was coming ?

History furnishes thousands of examples of men who have seized occasions to accomplish results deemed impossible by those less resolute- Prompt decision and whole-souled action sweep the world before them.

True, there has been but one Napoleon; but, on the other hand, the Alps that oppose the progress of the average American youth are not as high or dangerous as the summits crossed by the Corsican.

Don't wait for extraordinary opportunities- Seize common occasions and make them great.

On the morning of September 6, 1838, a young woman in the Longstone Lighthouse, between England and Scotland, was awakened by shrieks of agony rising above the roar of wind and wave. A storm of unwonted fury was raging, and her parents could not hear the cries; but a telescope showed nine human beings clinging to the windlass of a wrecked vessel whose bow was hanging on the rocks half a mile away. " We can do no

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 9

thing," said William Darling, the light-keeper. "Ah, yes, we must go to the rescue," exclaimed his daughter, pleading tearfully with both father and mother until the former replied: "Very well, Grace, I will let you persuade me, though it is against my better judgment." Like a feather in a whirlwind the little boat was tossed on the tumultuous sea, and it seemed to Grace that she could feel her brain reel amid the maddening swirl. But borne on the blast that swept the cruel surge, the shrieks of those shipwrecked sailors seemed to change her weak sinews into cords of steel. Strength hitherto unsuspected came from somewhere, and the heroic girl pulled one oar in even time with her father.

At length the nine were safely on board. "God bless you; but ye're a bonny English lass," said one poor fellow, as he looked wonderingly upon this marvelous girl, who that day had done a deed which added amore to England's glory than the exploits of many of, her monarchs.

A cat-boat was capsized in 1854 near Lime Rock Lighthouse, Newport, R. I., and four young men were left struggling in the cold waves of a choppy sea. Keeper Lewis was not at home, and his sick wife could do, nothing; but their daughter Ida, twelve years old, rowed out in a small boat and saved the men. During the next thirty years she rescued nine other, at various times. Her work was done without assistance, and showed skill and endurance fully equal to her great courage.

"If you will let me try, I think I can make some thing that will do," said a boy who had been employed as a scullion at the mansion of Signor Faliero, as the story is told by George Cary Eggleston. A large company had been invited to the banquet, and just before the hour the confectioner, who bad been making a large ornament for the table, sent word that he had spoiled the piece. " You !" exclaimed the head servant, in astonishment; " and who are you ?" " I am Antonio

10 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

Canova, the grandson of Pisano the stone-cutter," replied the pale-faced little fellow.

"And, pray, what can you do ?" asked the major domo- "I can make you something that will do for the middle of the table, if you'll let me try." The servant was at his wit's end, so he told Antonio to go ahead and see what he could do. Calling for some butter, the scullion quickly moulded a large crouching lion, which the admiring major-domo placed upon the table.

Dinner was announced, and many of the most noted merchant's, princes, and noblemen of Venice were ushered into the dining-room. Among them were skilled critics of art work. When their eyes fell upon the butter lion, they forgot the purpose for which they had come, in their wonder at such a work of genius. They looked at the lion long and carefully, and asked Signor Faliero what great sculptor had been persuaded to waste his skill upon a work in such a temporary material. Faliero could not tell; so he asked the head servant, who brought Antonio before the company.

When the distinguished guests learned that the lion had been made in a short time by a scullion, the dinner was turned into a feast in his honor. The rich host declared that he would pay the boy's expenses under the best masters, and he kept his word. But Antonio was not spoiled by his good fortune." He remained at heart the same simple, earnest, faithful boy, who had tried so hard to become a good stone-cutter in the shop of Pisano. Some may not have heard how the boy Antonio took advantage of this first great opportunity; but all know of Canova, one of the greatest sculptors of all time.

Weak men wait for opportunities, strong men make them. "The best men," says E. H. Chapin, "are not those who have waited for chances but who have taken them; besieged the chance; conquered the chance; and made chance the servitor."

" Oh, how I wish I were rich I " exclaimed a bright,

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 11

industrious drayman in Philadelphia, who had many mouths to fill at home. "Well, why don't you get rich ?" asked Stephen Girard, who had overheard the remark. "I don't know how, without money," replied the drayman. "You don't need money," replied Mr. Girard. " Well, if you will tell me how to get rich without money, I won't let the grass grow before trying it."

"A ship-load of confiscated tea is to be sold at, auction tomorrow at the wharf," said the millionaire. "Go down and buy it, and then come to me." "But I have no money to buy a whole ship-load of tea,, "with," protested the drayman. "You don't need any money, I tell you," said Girard sharply; "go down and bid on the

whole cargo, and then come to me."

The next day the auctioneer said that purchasers would have the privilege of taking the one case, or the whole ship-load, buying by the pound. A retail grocer started the bidding, and the drayman at once named a higher figure, to the surprise of the large crowd present. "I'll take the whole ship-load," said he coolly, when a sale was announced. The auctioneer was astonished, but when he learned that the young bidder was Mr. Girard's drayman, his manner changed, and he said it was probably all right.

The news spread that Girard was buying tea in large quantities, and the price rose several cents per pound. "Go and sell, our tea," said the great merchant the next day. The young man secured quick sales by quoting a price a trifle below the market rate, and in a few hours he was worth fifty thousand dollars.

The author does not endorse this method of doing business, but tells the story merely as an example of seizing an opportunity. There may not be one chance in a million that you will ever receive aid of this kind; but opportunities are often presented which you can improve to good advantage, if you will only act.

12 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

"'You are too young," said the advertiser for a factory manager in Manchester, England, after a single glance at an applicant. "They used to object to me on that score four or five years ago," replied Robert Owen, "but I did not expect to have it brought up now." "How often do you get drunk in the week ? " "I never was drunk in my life," said Owen, blushing. " What salary do ' you ask ? " "Three hundred (pounds) a year" " Three hundred a year! Why I have had I don't know how many after the place here this morning, and all their asking together would not come up to what you want."

" Whatever others may ask, I cannot take less. I am making there hundred a year by my own business." The youth, who had never been in a large cotton mill, was put in charge of a factory employing five hundred operatives. By studying machines, cloth, and processes at night, he mastered every detail of the business in a short time, and was soon without a superior in his line in Manchester.

The lack of opportunity is ever the excuse of a weak, vacillating mind. Opportunities ! Every life is full of them. Every lesson in school or college is an opportunity. Every examination is a chance in life. Every patient is an opportunity. Every newspaper article is an opportunity. Every client is an opportunity. Every sermon is an opportunity. Every business transaction is an opportunity, - an opportunity to be polite, - an opportunity to be manly, - an opportunity to be honest, - an opportunity to make friends. Every proof of confidence in you is a great opportunity. Every responsibility thrust upon your strength and your honor is priceless. Existence is the privilege of effort, and then that privilege is met like a man, opportunities to succeed along the line of your aptitude will come faster than you can use them. If a slave like Fred Douglass can elevate himself into an orator, editor, statesman

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 13

what ought the poorest white boy to do, who is rich in opportunities compared with Douglass, who did not even own his body ?

It is the idle man, not the great worker; who is always complaining that he has no time or opportunity. Some young men will make more out of the odds and ends of opportunities, which many carelessly throw away, than others will get out of a whole lifetime. Like bees, they extract honey from every flower. Every person they meet, every circumstance of the day, must add something to their store of useful knowledge or personal power. "

"There is nobody whom Fortune does not visit once in his life," says a Cardinal; "but when she finds he is not ready to receive her, she goes in at the door and out at the window."

"What is its name?" asked a visitor in a studio, when shown, among many gods, one whose face was concealed by hair, and which had wings on its feet. "Opportunity," replied the sculptor. "Why is its face hidden?" "Because men seldom know him when becomes to them." "Why has he wings on his feet? " "Because he is soon gone, and once gone, cannot be overtaken"

Life pulsates with chances. They may not be dramatic or great, but they are important to him who would get on in the world.

Cornelius Vanderbilt saw his opportunity in the steamboat, and determined to identify himself with steam navigation. To the surprise of all his friends, he abandoned his prosperous business and took command of one of the first steamboats launched, at one thousand dollars a year. Livingston and Fulton had acquired the sole right to navigate New York waters by steam, but Vanderbilt thought the law unconstitutional, and defied it until it was repealed. He soon became a steamboat owner. When the government was paying a

14 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

large subsidy for carrying the European mails, he offered to carry them free and give better service. His offer was accepted, and in this way he soon built up an enormous freight and passenger traffic. Foreseeing the great future of railroads in a country like ours, he plunged into railroad enterprises with all his might, laying the foundation for the vast Vanderbilt system of today.

Young Philip Armour joined the long caravan of Forty Niners, and crossed the "Great American Desert" with all his possessions in a prairie schooner drawn by mules. Hard work and steady gains carefully saved in the mines enabled him to start, six years later, in the grain and warehouse business in Milwaukee.

In nine years he made five hundred thousand dollars. But he saw his great opportunity in Grant's order, " On to Richmond." One morning in 1864, he knocked at the door of Plankinton, partner in his venture as a pork packer. " I am going to take the next train to New York," said he, "to sell pork ' short.' Grant and Sherman have the rebellion by the throat, and pork will go down to twelve dollars a barrel." This was his opportunity.

He went to New York and offered pork in large quantities at forty dollars per barrel. It was eagerly taken. The shrewd Wall Street speculators laughed at the young Westerner, and told him pork would go to sixty dollars, for the war was not nearly over. Mr. Armour kept on selling. Grant continued to advance. Richmond fell, and pork fell with it to twelve dollars a barrel. Mr. Armour cleared two millions of dollars.

John D. Rockefeller saw his opportunity in petroleum. He could see a large population in this country, with very poor lights. Petroleum was plenty, but the refining process was so crude that the product was inferior, and not wholly safe. Here was his chance. Taking into partnership Samuel Andrews, the porter in a mashine shop where both had worked, Mr. Rockefeller

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 15

started a single barrel still in 1870, using an improved process discovered by his partner. They made a superior grade of oil and prospered rapidly. They soon admitted the third partner, Mr. Flagler, but Andrews soon became dissatisfied.

"What will you take for your interest ? " asked Rockefeller. Andrews wrote carelessly on a piece of paper, " One million dollars." Within twenty-four hours Mr. Rockefeller handed him the amount, saying, "Cheaper at one million than ten." In twenty years the business of the little refinery, not worth one thousand dollars for building and apparatus, had grown into the Standard Oil Trust, capitalized at ninety millions of dollars, with stock quoted at 170, giving a market value of one hundred and fifty millions.

These are illustrations of seizing opportunity for the purpose of making money. But fortunately there is a new generation of electricians, of engineers, of scholars, of artists, of authors, and of poets, who find opportunities, thick as thistles, for doing something nobler than merely becoming rich-' Wealth is not an end to strive for, but an opportunity; not the climax of a man's career, but the beginning.

Mrs. Elizabeth Fry, a Quaker lady, saw her opportunity in the prisons of England. From three hundred to four hundred half-naked women, as late as 1813, would often be huddled in a single ward of Newgate, London, awaiting trial. They had neither beds nor bedding, but women, old and young, and little girls, slept in filth and rags on the floor. No one seemed to care for them, and the Government furnished simply food to keep them alive. She visited Newgate, calmed the howling mob, and told them she wished to establish a school for the young women and the girls, and asked them to select a schoolmistress from their own number. They were amazed, but chose a young woman who had been committed for stealing a watch. In three months

16 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

these "wild beasts," as they were sometimes called, were tame, and became harmless and kind. The reform spread until the Government legalized the system, and good women throughout Great Britain became interested in the work of educating and clothing these outcasts. Fourscore years have passed, and her plan has been adopted throughout the civilized world.

A boy in England had been run over by the cars, and the bright blood spurted from a severed artery- No one seemed to know what to do until another boy, Astley Cooper, took his handkerchief and stopped the bleeding by pressure above the wound. The praise which Astley received for thus saving the boy's life encouraged him to become a surgeon, the foremost of his day.

" The time comes to the young surgeon," says Arnold, "when, after long waiting, and patient study and experiment, he is suddenly confronted with his first critical operation- The great surgeon is away. Time is pressing. Life and death hang in the balance. Is he equal to the emergency ? Can he fill the great surgeon's place, and do his work ? If he can, he is the one of all others who is wanted. His opportunity confronts him. He and it are face to face. Shall he confess his ignorance and inability, or step into fame and fortune ? It is for him to say."

Are you prepared for a great opportunity ? "Hawthorne dined one day with Longfellow," said James T- Fields, "and brought a friend with him from Salem. After dinner the friend said, ' I have been trying to persuade Hawthorne to write a story based upon a legend of Acadia, and still current there, - the legend of a girl who, in the dispersion of the Acadians, was separated from her lover, and passed her life in waiting and seeking for him, and only found him dying in a hospital when both were old.' Longfellow wondered that the legend did not strike the fancy of Hawthorne, and he said to him, ' If you have really made up your

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 17

mind not to use it for a story, will you let me have it for a poem ? ' To this Hawthorne consented, and promised, moreover, not to treat the subject in prose till Longfellow had seen what he could do with it in verse- Longfellow seized his opportunity and gave to the world Evangeline, or the Exile of the Acadians."'

Of what value was the old story of Shylock and his pound of flesh (contained in a dozen lines) till Shakespeare touched it with his magic pen and transformed it into a realistic drama ?

Open eyes will discover opportunities everywhere; open ears will never fail to detect the cries of those who are perishing for assistance; open hearts will never want for worthy objects upon which to bestow their gifts; open hands will never lack for noble work to do.

Everybody had noticed the overflow when a solid is immersed in a vessel filled with water, although no one had made use of his knowledge, that the body displaces its exact bulk of liquid; but when Archimedes observed the fact, he perceived therein an easy method of finding the cubical contents of objects, however irregular in shape. Everybody knew how steadily a suspended weight, when moved, sways back and forth until friction and the resistance of the air bring it to rest, yet no one considered this information of the slightest practical importance ; but the boy Galileo, as he watched a lamp left swinging by accident in the cathedral at Pisa, saw in the regularity of those oscillations the useful principle of the pendulum: Even the iron doors of a prison were not enough to shut him out from research, for he experimented with the straw of his cell, and learned valuable lessons about the relative strength of tubes and rods of equal diameters. For ages astronomers had been familiar with the rings of Saturn, and regarded them merely as curious exceptions to the supposed law of planetary formation; but Laplace saw that, instead of being exceptions, they are the sole remaining visible evidences

18 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

of certain stages in the invariable process of star manufacture, and from their mute testimony he added a valuable chapter to the scientific history of Creation. There was not a sailor in Europe who had not wondered what might lie beyond the Western Ocean, but it remained for Columbus to steer boldly out into an unknown sea and discover a new world. Innumerable apples had fallen from trees, often hitting heedless men on the head as if to set them thinking, but not before Newton did any one realize that they fall to the earth by the same law which holds the planets in their courses, and prevents the momentum of all the atoms in the universe from hurling them wildly back to chaos. Lightning had dazzled the eyes, and thunder had jarred the ears of men since the days of Adam, in the vain attempt to call their attention to the all-pervading and tremendous energy of electricity; but the discharges of Heaven's artillery were seen and heard only by the eye and ear of terror until Franklin, by a simple experiment, proved that lightning is but one manifestation of a resistless yet controllable force, abundant as air and water.

Like many others, these men are considered great, simply because they improved opportunities common to the whole human race. Read the story of any successful man and mark its moral, told thousands of years ago by Solomon: " Seest thou a man diligent in his business ? he shall stand before kings." This proverb is well illustrated by the career of the industrious Franklin, for he stood before five kings and dined with two.

He who improves an opportunity sows a seed which will yield fruit in opportunity for himself and others. Every one who has labored honestly in the past has aided to place knowledge and comfort within. the reach of a constantly increasing number.

Avenues greater in number, wider in extent, easier of access than ever before existed, stand open to the sober, frugal, energetic and able mechanic, to the educated

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY. 19

youth, to the office boy and to the clerk-avenues through which they can reap greater successes than ever before within the reach of these classes within the history of the world. A little while ago there were only three or four professions -now there are fifty. And of trades, where there was one, there are a hundred now.

"Opportunity has hair in front," says a Latin author .,- "behind she is bald; if you seize her by the forelock, you may hold her, but, if suffered to escape, not Jupiter himself can catch her again."

But what is the best opportunity to. him who cannot or will not use it ? "It was my lot," said a shipmaster, "to fall in with the ill-fated steamer Central America. The night was closing in, the sea rolling high; but I hailed the crippled steamer and asked if they needed help. ' I am in a sinking condition,' cried Captain Herndon. ' Had you not better send your passengers on board directly ?.' I asked. ' Will you not lay by me until morning ? ' replied Captain Herndon. ' I will try,' I answered, ' but had you not better send your passengers on board now ?" ' Lay by me till morning,' again shouted Captain Herndon. "I tried to lay by him, but at night, such was the heavy roll of the sea, I could not keep my position, and I never saw the steamer again. In an hour and a half after the Captain said, ' Lay by me till morning,' his vessel, with its living freight, went down. The Captain and crew and most of the passengers found a grave in the deep."

Captain Herndon appreciated the value of the opportunity he had neglected when it was beyond his reach, but of what avail was the bitterness of his self-reproach when his last moments came ? How many lives were sacrificed to his unintelligent hopefulness and indecision! Like him the feeble, the sluggish, and the purposeless too often see no meaning in the happiest

20 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

occasions, until too late they learn the old lesson that the mill can never grind with the water which has passed. Such people are always a little too late or a little too early in everything they attempt. "They have three hands apiece," said John B- Gough ; " a right hand, a left hand, and a little behind-hand."

As boys, they were late at school, and unpunctual in their home duties. That is the way the habit is acquired; and now, when responsibility claims them, they think that if they had only gone yesterday they would have obtained the situation, or they can probably get one tomorrow. They remember plenty of chances to make money, or know how to make it some other time than now; they see how to improve themselves or help others in the future, but perceive no opportunity in the present. They are always at the pool, but somehow, when the angel troubles the water, there is no one to put them in. They cannot seize their opportunity.

Joe Stoker, rear brakeman on the accommodation train, was exceedingly popular with all the railroad men. The passengers liked him, too, for he was eager to please and always ready to answer questions. But he did not realize the full responsibility of his position- He " took the world easy," and occasionally tippled; and if any one remonstrated, he would give one of his brightest smiles, and reply in such a good-natured way that the friend would think he had overestimated the danger: "Thank you- I'm all right. Don't you worry." One evening there was a heavy snowstorm, and his train was delayed. Joe complained of extra duties because of the storm, and slyly sipped occasional draughts from a flat bottle. Soon be became quite jolly; but the conductor and engineer of the train were both vigilant and anxious.

Between two stations the train came to a quick halt; The engine had blown out its cylinder head, and an express was due in a few minutes upon the same track

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY 21

The conductor hurried to the rear car, and ordered Joe back with a red light. The brakeman laughed and said " There's no hurry. Wait till I get my overcoat." The conductor answered gravely, "Don't stop a minute, Joe. The express is due."

"All right," said Joe, smilingly. The conductor then hurried forward to the engine. But the brakeman did not go at once- He stopped to put on his overcoat. Then he took another sip from the flat bottle to keep the cold out- Then he slowly grasped the lantern and, whistling, moved leisurely down the track.

He had not gone ten paces before he heard the puffing of the express. Then he ran for the curve, but it was too late. In a horrible minute the engine of the express had telescoped the standing train, and the shrieks of the mangled passengers mingled with the hissing escape of steam.

Later on, when they asked for Joe, he had disappeared ; but the next day he was found in a barn, delirious, swinging an empty lantern in front of an imaginary train, and crying, " Oh, that I had! "

He was taken home, and afterward to an asylum, for this is a true story, and there is no sadder sound in that sad place than the unceasing moan, " Oh, that I 'had! " " Oh, that I bad! " of the unfortunate brakeman, whose criminal indulgence brought disaster to many lives.

" Oh, that I had!" or "Oh, that I had not!" is the silent cry of many a man who would give life itself for the opportunity to go back and retrieve some long-past error.

"There are moments," says Dean Alford, " which are worth more than years. We cannot help it. There is no proportion between spaces of time in importance nor in value - A stray, unthought of five minutes may contain the event of a life. And this all-important moment - who can tell when it will be upon us ? "

22 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

"What we call a turning-point," says Arnold, " is simply an occasion which sums up and brings to a result previous training. Accidental circumstances are nothing except to men who have been trained to take advantage of them." An opportunity will only make you ridiculous unless you are prepared for it.

The trouble with us is that we are ever looking for a princely chance of acquiring riches, or fame, or worth. We are dazzled by what Emerson calls the " shallow Americanism" of the day. We are expecting mastery without apprenticeship, knowledge without study, and riches by credit. Because the politician acquires power by bribing the caucus, influence by "standing in" with the saloon keeper, wealth by fraud, and immunity from conviction by packing the jury, we are cozened into looking at life through a distorted lens. These are opportunities to be shunned like the cholera. They appear to rest upon a solid foundation, but they lead to infamy, and crime, and harmfulness to mankind, and perhaps suicide.

It is a common saying that "Luck beats science every time." But this is the gambler's maxim, the fool's motto.

Young men and women, why stand ye here all the day idle ? Was the land all occupied before you were born ? Has the earth ceased to yield its increase ? Are the seats all taken ? the positions all filled ? the chances all gone ? Are the resources of your country fully developed ? Are the secrets of nature all mastered ? Is there no way in which you can utilize these passing moments to improve yourself or benefit another ? Is the competition of modern existence so fierce that you must be content to simply gain an honest living ? Have you received the gift of life in this progressive age, wherein all the experience of the past is garnered for your inspiration, merely that you may increase by one the sum total of purely animal existence ?

THE MAN AND THE OPPORTUNITY 23

The new is supplanting the old everywhere. The machinery of ten years ago must soon be sold as old iron to make room for something more efficient. The methods of our fathers are daily giving place to better systems. Those who have devoted their lives to the cause of labor and progress are constantly falling in the ranks; and, as the struggle grows more intense, men and women with even stronger arms and truer hearts are needed to take the vacant places in the Battle of Life.

Born in an age and country in which knowledge and opportunity abound as never before, how can you sit with folded hands, asking God's aid in work for which He has already given you the necessary faculties and strength ? Even when the Chosen People supposed their progress checked by the Red Sea, and their leader paused for Divine help, the Lord said, " Wherefore criest thou unto me? Speak unto the children of Israel, that they go forward."

With the world full of work that needs to be done; with human nature so constituted that often a pleasant word or a trifling assistance may stem the tide of disaster for some fellow man, or clear his path to success; with our own faculties so arranged that in honest, earnest, persistent endeavor we find our highest good; and with countless noble examples to encourage us to dare and to do, each moment brings us to the threshold of some new opportunity.

Don't wait for your opportunity. Make it, - make it as the shepherd-boy Ferguson made his when he calculated the distances of the stars with a handful of glass beads on a string. Make it as George Stephenson made his when he mastered the rules of mathematics with a bit of chalk on the grimy sides of the coal wagons in the mines. Make it, as Napoleon made his in a hundred " impossible " situations. Make it, as all leaders of men, in was and in peace, have made their

24 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

chances of success. Make it, as every man must, who would accomplish anything worth the effort. Golden opportunities are nothing to laziness, but industry makes the commonest chances golden.

" There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.,,

" IT is never offered twice seize, then, the hour

When fortune smiles, and duty points the way;

Nor shrink aside to 'scape the spectre fear,

Nor pause, though pleasure beckon from her bower;

But bravely bear thee onward to the goal.'

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

| "Seest thou a man diligent in his business. He shall stand before kings." "I have made the most out of the stuff." |

CHAPTER II.

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE.

In the blackest soils grow the fairest flowers, and the loftiest and strongest trees spring heavenward among the rocks. - J. G. HOLLAND.

Poverty is very terrible, and sometimes kills the very soul within us, but it is the north wind that lashes men into Vikings; it is the soft, luscious south wind which lulls them to lotus dreams. - OUIDA.

Want is a bitter and a hateful good,

Because its virtues are not understood;

Yet many things, impossible to thought,

Have been by need to full perfection brought.

The daring of the soul proceeds from thence

Sharpness of wit and active diligence.

Prudence at once and fortitude it gives,

And if in patience taken, mends our lives.

DRYDEN.

Poverty is the sixth sense. -GERMAN PROVERB.

It is not every calamity that is a curse, and early adversity is often a blessing. Surmounted difficulties not only teach, but hearten us in our future struggles. - SHARPE.

There can be no doubt that the captains of industry today, using that term in its broadest sense, are men who began life as poor boys. - SETH LOW.

'Tis a common proof, That lowliness is young ambition's ladder! - SHAKESPEARE.

"I AM a child of the court," said a pretty little girl at a children's party in Denmark; "my father is Groom of the Chambers, which is a very high office. And those whose names end with "sen,"' she added, "can never be anything at all. We must put our arms akimbo, and make the elbows quite pointed, so as to keep these 'sen' people at a great distance."

"But my papa can buy a hundred dollars' worth of bonbons, and give them away to children," angrily exclaimed the daughter of the rich merchant Petersen. "Can your papa do that !"

26 PUSHING TO THE FRONT

"Yes," chimed in the daughter of an editor, "my papa can put your papa and everybody's papa into the newspaper. All sorts of people are afraid of him, my papa says, for he can do as he likes with the paper."

Oh, if I could be one of them ! " thought a little boy peeping through the crack of the door, by permission of the cook for whom he had been turning the spit. But no, his parents had not even a penny to spare, and his name ended in "sen."

Years afterwards, when the children of the party had become men and women, some of them went to see a splendid house, filled with all kinds of beautiful and valuable objects. There they met the owner, once the very boy who thought it so great a privilege to peep at them through a crack in the door as they played. He had become the great sculptor Thorwaldsen.

This sketch is adapted from a story by a poor Danish cobbler's boy, whose name did not keep him from becoming famous, - Hans Christian Andersen.

" There is no fear of my starving, father," said the deaf boy, Kitto, begging to be taken from the poorhouse and allowed to struggle for an education; "we are in the midst of plenty, and I- know how to prevent hunger. The Hottentots subsist a long time on nothing but a little gum; they also, when hungry, tie a ligature around their bodies. Cannot I do so, too? The hedges furnish blackberries and nuts, and the fields, turnips; a hayrick will make an excellent bed." This poor deaf boy with a drunken father, who was thought capable of nothing better than making shoes as a pauper, became one of the greatest biblical scholars in the world. His first book was written in the workhouse.

Creon was a Greek slave, as a writer tells the story in Kate Field's " Washington," but he was also a slave of the Genius of Art. Beauty was his god, and he worshiped it with rapt adoration. It was after the

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE 27

repulse of the great Persian invader, and a law was in force, that under penalty of death no one should espouse art except freemen. When the law was enacted he was engaged upon a group for which he hoped some day to receive the commendation of Phidias, the greatest sculptor living, and even the praise of Pericles.

What was to be done ? Into the marble block before him Creon had put his head, his heart, his soul, his life. On his knees, from day to day, he had prayed for fresh inspiration, new skill. He believed, gratefully and proudly, that Apollo, answering his prayers, had directed his hand and had breathed into the figures the life that seemed to animate them; but now, - now, all the gods seemed to have deserted him.

Cleone, the devoted sister of Creon, felt the blow as deeply as her brother. "O Aphrodite !" she prayed, "immortal Aphrodite, high enthroned child of Zeus, my queen, my goddess, my patron, at whose shrine I have daily laid my offerings, be now my friend, the friend of my brother! "

Then to her brother she said: " O Creon, go to the cellar beneath our house. It is dark, but I will furnish light and food. Continue your work; the gods will befriend us." To the cellar Creon went, and guarded and attended by his sister, day and night, he proceeded with his glorious but dangerous task.

About this time all Greece was invited to Athens to behold an exhibit of works of art. The display took place in the Agora. Pericles presided. At his side was Aspasia. Phidias, Socrates, Sophocles, and other renowned men stood near him. The works of the great masters were there. But one group, far more beautiful than the rest, - a group that Apollo himself must have chiseled, - challenged universal attention, exciting at the same time no little envy among rival artiste.

28 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

"Who is the sculptor of this group ? " None could tell. Heralds repeated the question, but there was no answer. "A mystery, then ! Can it be the work of a slave ?" Amid great commotion a beautiful maiden with disarranged dress, disheveled hair, a determined expression in her eyes, and with closed lips, was dragged into the Agora. "This woman," cried the officers, "this woman knows the sculptor; we are sure of this; but she will not tell his name."

Cleone was questioned, but was silent. She was informed of the penalty of her conduct, but her lips remained closed. "Then," said Pericles, "the law is imperative, and I am the minister of the law. Take the maid to the dungeon."

As he spoke, a youth with flowing hair, emaciated, but with black eyes that beamed with the flashing light of genius, rushed forward, and flinging himself before Pericles, exclaimed: " O Pericles, forgive and save the maid. She is my sister. I am the culprit. The group is the work of my hands, the hands of a slave."

The indignant crowd interrupted him and cried, "To the dungeon, to the dungeon with the slave." " As I live, no! " said Pericles rising. "Behold that group ! Apollo decides by it that there is something higher in Greece than an unjust law. The highest purpose of law should be the development of the beautiful. If Athens lives in the memory and affections of men, it is her devotion to art that will immortalize her. Not to the dungeon, but to my side bring the youth."

And there, in the presence of the assembled multitude, Aspasia placed the crown of olives, which she held in her hands, on the brow of Creon ; and at the same time, amid universal 'plaudits, she tenderly kissed Creon's affectionate and devoted sister.

The Athenians erected a statue to Aesop, who was born a slave, that men might know that the way to honor is open to all. In Greece, wealth and immortality

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE 29

were the sure reward of the man who could distinguish himself in art, literature, or war. No other country ever did so much to encourage and inspire struggling merit. Genius, achievement, beauty, were worshiped by the Greeks.

"I was born in poverty," said Vice-President Henry Wilson. "Want sat by my cradle. I know what it is to ask a mother for bread when she has none to give. I left my home at ten years of age, and served an apprenticeship of eleven years, receiving a month's schooling each year, and, at the end of eleven years of hard work, a yoke of oxen and six sheep, which brought me eighty-four dollars. I never spent the sum of one dollar for pleasure, counting every penny from the time I was born till I was twenty-one years of age. I know what it is to travel weary miles and ask my fellow men to give me leave to toil. In the first month after I was twenty-one years of age, I went into the woods, drove a team, and cut mill-logs. I rose in the morning before daylight and worked hard till after dark, and received the magnificent sum of six dollars for the month's work! Each of these dollars looked as large to me as the moon looks tonight."

Mr. Wilson determined to never lose an opportunity for self-culture or self-advancement. Few men knew so well the value of spare moments. He seized them as though they were gold and would not let one pass until he had wrung from it every possibility. He managed to read a thousand good books before he was twenty-one -what a lesson for boys on a farm! When he left the farm he started on foot for Natick, Mass., over one hundred miles distant, to learn the cobbler's trade. He went through Boston that he might see Bunker Hill monument and other historical landmarks. The whole trip cost him but one dollar and six cents.

In a year he was at the head of a debating club at Natick. Before eight years had passed, he made his great speech against

30 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

slavery, in the Massachusetts Legislature. Twelve years later he stood shoulder to shoulder with the polished Sumner in Congress. With him, every occasion was a great occasion. He ground every circumstance of his life into material for success.

" Don't go about the town any longer in that outlandish rig. Let me give you an order on the store. Dress up a little, Horace" Horace Greeley looked down on his clothes as if he had never before noticed how seedy they were, and replied: " You see, Mr. Sterrett, my father is on a new place, and I want to help him all I can."

He had spent but six dollars for personal expenses in seven months, and was to receive one hundred and thirty-five from Judge J. M. Sterrett of the Erie "Gazette" for substitute work. He retained but fifteen dollars and gave the rest to his father, with whom he had moved from Vermont to Western Pennsylvania, and for whom he had camped out many a night to guard the sheep. from wolves. He was nearly twenty-one; and, although tall and gawky, with tow-colored hair, a pale face and whining voice, he resolved to seek his fortune in New York City. Slinging his bundle of clothes on a stick over his shoulder, he walked sixty miles through the woods to Buffalo, rode on a canal boat to Albany, descended the Hudson in a barge, and reached New York, just as the sun was rising, August 18, 1831.

He found board over a saloon at two dollars and a half a week. His journey of six hundred miles had cost him but five dollars. For days Horace wandered up and down the streets, going into scores of buildings and asking if they wanted "a hand;" but "no" was the invariable reply. His quaint appearance led many to think he was an escaped apprentice. One Sunday at his boarding-place he heard that printers were wanted at " West's Printing-office." He was at the door at five o'clock Monday morning, and asked the foreman for a

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE. 31

job at seven. The latter had no idea that the country greenhorn could set type for the Polyglot Testament on which help was needed, but said: "Fix up a case for him and we'll see if he can do anything."

When the proprietor came in, he objected to the newcomer and told the foreman to let him go when his first day's work was done. That night Horace showed a proof of the largest and most correct day's work that had then been done. In ten years Horace was a partner in a small printing-office. He founded the " New Yorker," the best weekly paper in the United States, but it was not profitable.

When Harrison was nominated for President in eighteen hundred and forty, Greeley started "The Log-Cabin," which reached the then fabulous circulation of ninety thousand.

But on this paper at a penny a copy, he made no money. His next venture was "The New York Tribune," price one cent. To start it he borrowed a thousand dollars and printed five thousand copies of the first number. It was difficult to give them all away.

He began with six hundred subscribers, and increased the list to eleven thousand in six weeks. The demand for the " Tribune " grew faster than new machinery could be obtained to print it. It was a paper whose editor, whatever his mistakes, always tried to be right.

James Gordon Bennett had made a failure of his "New York Courier" in eighteen hundred twenty-five, of the "Globe" in eighteen hundred thirty-two, and of the "Pennsylvanian" a little later, and was only known as a clever writer for the press, who had saved a few hundred dollars by hard labor and strict economy for fourteen years. In eighteen hundred thirty-five he asked Horace Greeley to join him in starting a new daily paper, the "New York Herald." Greeley declined, but recommended two young printers, who formed a partnership with Bennett, and the "Herald" was started May 6, eighteen hundred thirty-five, with a

32 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

cash capital sufficient to pay expenses for ten days. Bennett hired a small cellar on Wall Street, furnished it with a chair and a desk composed of a plank supported. by two barrels; and there, doing all the work except the printing, began the work of making a really great daily newspaper, a thing then unknown in America, as all its predecessors were party organs. Steadily the young man struggled towards his ideal, giving the news, fresh and crisp, from an ever widening area, until his paper was famous for giving the current history of the world as fully and quickly as any competitor, and often much more thoroughly and far more promptly. Neither labor nor expense was spared in obtaining prompt and reliable information on every topic of general interest. It was an uphill job, but its completion was finally marked by the opening at the corner of Broadway and Ann Street of the most complete newspaper establishment then known.

One of the first things that attracts the attention on entering George W. Child's private office in Philadelphia is this motto, which was the keynote of the success of a boy who started with " no chance: " " Nihil sine labore." It was his early ambition to own the " Philadelphia Ledger " and the great building in which it was published; but how could a poor boy working for $2.00 a week ever hope to own such a great paper ? However, he had great determination and indomitable energy; and as soon as he had saved a few hundred dollars as a clerk in a bookstore, he began business as a publisher. He made " great hits " in some of the works he published, such as "Kane's Arctic Expedition." He had a keen sense of what would please the public, and there seemed no end to his industry.

In spite of the fact that the "Ledger " was losing money every day, his friends could not dissuade him from buying it, and in eighteen hundred sixty-four the dreams of his boyhood found fulfillment. He doubled

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE. 33

the subscription price, lowered the advertising rates, to the astonishment of everybody, and the paper entered upon a career of remarkable prosperity, the profits sometimes amounting to over four hundred thousand dollars a year. He always refused to lower the wages of his employees even when every other establishment in Philadelphia was doing so.

At a banquet in Lyons, nearly a century and a half ago, a discussion arose in regard to the meaning of a painting representing some scene in the mythology or history of Greece. Seeing that the discussion was growing warm, the host turned to one of the waiters and asked him to explain the picture. Greatly to the surprise of the company, the servant gave a clear and concise account of the whole subject, so plain and convincing that it at once settled the dispute.

"In what school have you studied, Monsieur?" asked one of the guests, addressing the waiter with great respect. "I have studied in many schools, Monseigneur," replied the young servant: "but the school in which I studied longest and learned most is the school of adversity." Well had he profited by poverty's lessons; for, although then but a poor waiter, all Europe soon rang with the fame of the writings of the greatest genius of his age and country, Jean Jacques Rousseau.

The smooth sand beach of Lake Erie constituted the foolscap on which, for want of other material, P. R. Spencer, a barefoot boy with no chance, perfected the essential principles of the Spencerian system of penmanship, the most beautiful exposition of graphic art.

With thirteen halfpence in his pocket William Cobbett started on foot to find work in the King's Gardens at Kew. "When my little fortune had been reduced to threepence," he says, " I was trudging through Richmond in my blue smock-frock and my red garters tied under my knees, when, staring about me, my eyes fell upon a little book in a bookseller's window, on the

34 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

outside of which was written, "The Tale of a Tub, Price 3d." The title was so odd that my curiosity was excited. I had threepence, but then I could not have any supper. In I went and got the little book, which I was so impatient to read, that I got over into a field at the upper corner of Kew Gardens, where there stood a haystack."

Here he read until he fell asleep, to be awakened by the birds at dawn. He found work at Kew, and for eight years followed the plough, when he ran away to London, copied law papers for eight or nine months, and enlisted in an infantry regiment. During his first year of soldier life he subscribed to a circulating library at Chatham, read every book in it, and began to study.

"I learned grammar when I was a private soldier on the pay of sixpence a day. The edge of my berth, or that of the guard-bed, was my seat to study in; my knapsack was my bookcase; a bit of board lying on my lap was my writing-table, and the task did not demand anything like a year of my life. I had no money to purchase candles or oil; in winter it was rarely that I could get any evening light but that of the fire, and only my turn, even, of that.

To buy a pen or a sheet of paper I was compelled to forego some portion of my food, though in a state of half starvation. I had no moment of time that I could call my own, and I had to read and write amidst the talking, laughing, singing, whistling, and bawling of at least half a score of the most thoughtless of men, and that, too, in the hours of their freedom from all control.

Think not lightly of the farthing I had to give, now and then, for pen, ink, or paper. That farthing was, alas! a great sum to me I was as tall as I am now, and I had great health and great exercise. The whole of the money not expended for us at market was twopence a week for each man. I remember, and well I may ! that upon one occasion I had, after all absolutely necessary expenses, on a Fri-

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE. 35

day, made shift to have a halfpenny in reserve, which I had destined for the purchase of a red herring in the morning, but when I pulled off my clothes at night, so hungry then as to be hardly able to endure life, I found that I had lost my halfpenny. I buried my head under the miserable sheet and rug, and cried like a child."

But Cobbett made even his poverty and hard circumstances serve his all-absorbing passion for knowledge and success. "If I," said he, "under such circumstances could encounter and overcome this task, is there, can there be in the whole world, a youth to find any excuse for its nonperformance ? "

Humphry Davy had but a slender chance to acquire great scientific knowledge, yet he had true mettle in him, and he made even old pans, kettles, and bottles contribute to his success, as he experimented and studied in the attic of the apothecary-store where he worked.

"Many a farmer's son," says Thurlow Weed, "has found the best opportunities for mental improvement in his intervals of leisure while tending ' sap-bush.' Such, at any rate, was my own experience. At night you had only to feed the kettles and keep up the fires, the sap having been gathered and the, woodcut before dark. During the day we would always lay in a good stock of ' fat-pine' by the light of which, blazing bright before the sugar-house, in the posture the serpent was condemned to assume, as a penalty for tempting our first grandmother, I passed many a delightful night in reading.

I remember in this way to have read a history of the French Revolution, and to have obtained from it a better and more enduring knowledge of its events and horrors and of the actors in that great national tragedy, than I have received from all subsequent reading. I remember also how happy I was in being able to borrow the books of a Mr. Keyes after a two-mile tramp through the snow, shoeless, my feet swaddled in remnants of rag carpet."

36 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

"May I have a holiday tomorrow, father?" asked Theodore Parker one August afternoon. The poor Lexington millwright looked in surprise at his youngest son, for it was a busy time, but he saw from the boy's earnest face that he had no ordinary object in view, and granted the request. Theodore rose very early the next morning, walked through the dust ten miles to Harvard College, and presented himself as a candidate for admission.

He had been unable to attend school regularly since he was eight years old, but he had managed to go three months each winter, and had reviewed his lessons again and again as he followed the plough or worked at other tasks. All his odd moments had been hoarded, too, for reading useful books, which he borrowed. One book he could not borrow, but he felt that he must have it; so on summer mornings he rose long before the sun and picked bushel after bushel of berries, which he sent to Boston, and so got the money to buy that coveted Latin dictionary.

"Well done,, my boy! " said the millwright, when his son came home late at night and told of his successful examination; "but, Theodore, I cannot afford to keep you there !" "True, father," said Theodore, "I am not going to stay there; I shall study at home, at odd times, and thus prepare myself for a final examination, which will give me a diploma."

He did this; and, by teaching school as he grew older, got money to study for two years at Harvard, where he was graduated with honor. Years after, when, as the trusted friend and adviser of Seward, Chase, Sumner, Garrison, Horace Mann, and Wendell Phillips, his influence for good was felt in the hearts of all his countrymen, it was a pleasure for him to recall his early struggles and triumphs among the rocks and bushes of Lexington.

"The proudest moment of my life," said Elihu Burritt, "was when I had first gained the full meaning of the first fifteen lines of Homer's Iliad. I took a short

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE. 37

triumphal walk, in favor of that exploit." His father died when he was sixteen, and Elihu was apprenticed to a blacksmith in his native village of New Britain, Conn. He had to work at the forge ten or twelve hours a day; but while blowing the bellows, he would solve mentally difficult problems in arithmetic.

In a diary kept at Worcester, whither he went some ten years later to enjoy its library privileges, are such entries as these, - "Monday, June 18, headache, 40 pages Cuvier's ' Theory of the Earth,' 64 pages French, 11 hours' forging. Tuesday, June 19, 60 lines Hebrew, 30 Danish, 10 lines Bohemian, 9 lines Polish, 15 names of stars, 10 hours' forging. Wednesday, June 20, 25 lines Hebrew, 8 lines Syriac, 11 -hours' forging." He mastered 18 languages and 32 dialects. He became eminent as the " Learned Blacksmith," and for his noble work in the service of humanity. Edward Everett said of the manner in which this boy with no chance acquired great learning: "It is enough to make one who has good opportunities for education hang his head in shame."

The barefoot Christine Nilsson in remote Sweden had little chance, but she won the admiration of the world for her wondrous power of song, combined with rare womanly grace.

"Let me say in regard to your adverse worldly circumstances," says Dr. Talmage to young men, "that you are on a level now with those who are finally to succeed. Mark my words, and think of it thirty years from now. You will find that those who, thirty years from now, are the millionaires of this country, who are the orators of the country, who are the poets of the Country, who are the strong merchants of the country, who are the great philanthropists of the country, - mightiest in the church and state, - are now on a level with you, not an inch above you, and in straightened circumstances now.

38 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.

"No outfit, no capital to start with ? Young man, go down to the library and get some books, and read of what wonderful mechanism God gave you in your hand, in your foot, in your eye, in your ear, and then ask some doctor to take you into the dissecting-room and illustrate to you what you have read about, and never again commit the blasphemy of saying you have no capital to start with. Equipped ? Why, the poorest young man is equipped as only the God of the whole universe could afford to equip him."

A newsboy is not a very promising candidate for success or honors in any line of life. A young man can't set out in life with much less chance than when he starts his "daily" for a living. Yet the man who more than any other is responsible for the industrial regeneration of this continent, started in life as a newsboy on the Grand Trunk Railway. Thomas Alva Edison was then about fifteen years of age. He had already begun to dabble in chemistry, and had fitted up a small itinerant laboratory. One day, as he was performing some occult experiment, the train rounded a curve, and the bottle of sulfuric acid broke. There followed a series of unearthly odors and unnatural complications. The conductor, who had suffered long and patiently, now ejected the youthful devotee, and in the process of the scientist's expulsion added a resounding box upon the ear.

Edison passed through one dramatic situation after another - always mastering it - until he has attained at an early age the scientific throne of the world. When recently asked the- secret of his success, he said he had always been a total abstainer and singularly moderate in everything but work.

Daniel Manning, who was President Cleveland's first campaign manager and afterwards Secretary of the Treasury, started out as a newsboy with apparently the world against him. So did Thurlow Weed; so did

BOYS WITH NO CHANCE. 39

David B. Hill. New York seems to have been prolific in enterprising newsboys.

What nonsense for two uneducated and unknown youths who met in a cheap boarding house in Boston. to array themselves against an institution whose roots were embedded in the very constitution of our country, and which was upheld by scholars, statesmen, churches, wealth, and aristocracy, without distinction of creed or politics ! What chance had they against the prejudices and sentiment of a nation? But these young men were fired by a lofty purpose, and they were thoroughly in earnest. One of them, Benjamin Lundy, had already started in Ohio a paper called " The Genius of Universal Liberty," and had carried the, entire edition home on his back from the printing-office, twenty miles, every month.. He had walked four hundred miles on his way to Tennessee to increase his subscription list. He was no ordinary young man.

With William Lloyd Garrison, he started to prosecute his work more earnestly in Baltimore. The sight of the slave-pens along the principal streets; of vessel loads of unfortunates torn from home and family and sent to Southern ports; the heartrending scenes at the auction blocks, made an impression on Garrison never to be forgotten; and the young man whose mother was too poor to send him to school, although she early taught him to hate oppression, resolved to devote his life to secure the freedom of these poor wretches.

In the very first issue of his paper, Garrison urged an immediate emancipation, and called down upon his head the wrath of the entire community. He was arrested and sent to jail. John G. Whittier, a noble Friend in the North, was so touched at the news that, being too poor to furnish the money himself, he wrote to Henry Clay, begging him to release Garrison by paying the fine. After forty-nine days of imprisonment he was set free. Wendell Phillips said of him, "He was

40 PUSHING TO THE FRONT.